Part 1: The Art & Artists of Agatha Christie (IACF 2024)

- David Morris

- Sep 21, 2024

- 16 min read

At the 2024 International Agatha Christie Festival in Torquay, Devon, I presented my research into the world of first edition cover art. This article is the first of two parts that will share that presentation in its entirity. While this can't match attending the festival in person as the setting is spectacular (The Spanish Barn, Torre Abbey) and the crowd is energizing, I do hope you enjoy reading this as it was a labour of love to put it together. I also want to thank The Agatha Christie Archive for their support with the research. At the Festival it was a real honour to talk with Mathew Prichard prior to my talk and have him share with me that he was really looking forward to hearing it. I hope I didn't let him down! - David.

The Art and Artists of Agatha Christie.

Welcome to “The Art and Artists of Agatha Christie”. First of all I want to thank the International Agatha Christie Festival for extending the offer to me to speak again at this event and thank you all for coming to hear all about this part of the Agatha Christie legacy.

But first let me properly introduce myself. I am the author and researcher for all the articles on the website CollectingChristie.com - a website that provides insights to the world of collecting all things Christie – from paperbacks to first editions, from memorabilia to art and even experiences – like travelling to places Christie visited. I’ve also written articles for various organizations on Christie and have had the chance to be on various Christie-focused podcasts. I was born in Exeter so it always feels like a homecoming whenever I’m back in Devon. But now let’s get back to the topic at hand… The Art and Artists of Agatha Christie.

Preamble:

My goal today is to share with you insights into many of the iconic dust jackets that adorned Christie’s British & American first editions. I hope that you will find this information about the artists interesting given how many of them have remained in the shadows over the years. I’ll discuss how they helped to bring her books to life and shape the public's perception of her work. And I’ll also give insights into Christie’s connections with some of these artists, as well as how she influenced their design. With such a large amount of potential content, I won’t be able to discuss every book or artist, but as we take this journey together we’ll mostly go chronologically from her first book in 1920, focusing a little more on the earlier books, and occasionally jumping back and forth across the Atlantic. So, let’s dive in.

1920 – The Mysterious Affair at Styles. Artist: Dewey.

Her first published novel was The Mysterious Affair at Styles, and it was actually first published in New York in 1920. It wasn’t published in England until the following year. The publisher was John Lane the Bodley Head. While this was an established British firm, they had opened a New York branch in 1896 – and it was this branch that was tasked with launching Agatha Christie’s first book.

Part of this launch was to have a dust jacket created that would help promote and sell the book. While dust jackets first appeared in the mid-1800s, back then they served a practical reason – essentially to protect the book. But by the early 1900s a much more commercial purpose had evolved. Dust jackets could help sell books. If a picture was worth a 1000 words, then a well-designed dust jacket was worth many more. It could quickly and effectively inform the potential buyer not only of the author’s name and book title, but the artwork could provide a glimpse into the type of story and experience the reader may have. So, John Lane needed a jacket designed for Christie’s first book.

The artist hired was an American – Alfred James Dewey. Born in 1874 in Pennsylvania, Dewey had studied at the Philadelphia School of Industrial Art and Design. One of his earliest jobs was as a cartoonist for an American periodical. His work there landed him commissions with well-known magazines such as “Life” and “Harpers” which led to him to move to New York. Perhaps not unusual for an artist, he met his wife, Sally, when she posed for him for an illustration he was creating for “Life” magazine.

When World War I broke out, his artistic output was mostly focused on paintings for calendars and magazines. But many of these images focused on love and romance – known as ‘glamour cards’(below) - and became a staple of postcards sent between soldiers and their wives or girlfriends during the war. While the artist’s name may not have been well-known, his style likely became broadly recognizable.

During the war he also received his first commissions to create dust jackets. A sample of them are shown here – but as you can see below his style shifted over the years and you can see traits of some of these jackets in the one that he created for Christie. The cover he designed was quite dark and ominous – appropriate for a murder mystery novel - but the style would potentially be recognizable to many and I’m certain the publisher hoped it would draw the attention of the shopper. As you can see the publisher left Dewey’s signature in the artwork – something that didn’t happen for many other jacket artists.

Christie herself was pleased with the design. On the 24th October 1920, she wrote to B. W. Willet, one of the Directors at John Lane The Bodley Head saying:

Dear Mr. Willett,

I returned the cover which I think will do very well - Quite artistic and mysterious! I should like the book to come out soon - before Xmas - especially as the Greenwood trial is just coming on. I am very anxious to have it dedicated to my mother. I believe I did speak about that to you before - and you said it could be done.

There are a few interesting things to learn from this letter. First, the novel was published in the States a month earlier, so it appears Mr. Willett was seeking approval to use the same design for the British printing. But it also implies Christie likely didn’t pre-approve the US jacket. It’s also the only time that a US designed jacket was used on a British first edition, and one of only a handful of times that the same design was used on both sides of the Atlantic. Christie also got her wish that the book was dedicated to her mother, but not her hope that it be published in the UK before Christmas. The Bodley Head launched the book in the UK in January. Christie’s letter also shows that she saw the benefit of tying in the launch to an ongoing true-crime case – The Greenwood Trial was about a husband who was accused of killing his wife by poisoning her. While the trial took place in November, the similarities between the real-life case and Christie’s book probably helped generate interest.

As for Dewey – he never designed another Christie jacket – but shifted to painting landscapes and designing floats for the annual Pasadena (California) Tournament of Roses parade.

1923 – Murder on the Links. Artist: H.T. Warren.

Christie’s third novel, following The Secret Adversary, was The Murder on the Links. It was initially serialised under the title ‘The Girl with the Anxious Eyes’. Here is an excerpt from a letter to Mr. Willett – the Director of The Bodley Head. It shows us that Christie was engaged in the publication process – from discussing what title will be used and providing ideas for the jacket’s design:

I see that The Girl with The Anxious Eyes will be concluded in the February number of the Grand Magazine which is due out shortly. When are you publishing this in book form and under what title? I suggest for the cover a green patch of grass on the links, the grave and near it the man’s body with a dagger sticking out of it.

However, the proof jacket Christie received back clearly was nothing like this. As we can see from her autobiography, she wasn’t pleased with the design.

The Bodley Head were pleased with Murder on the Links, but I had a slight row with them over the jacket they had designed for it. Apart from being ugly colours, it was badly drawn, and represented, as far as I could make out, a man in pyjamas on a golf-links, dying of an epileptic fit. Since the man who had been murdered had been fully dressed and stabbed with a dagger, I objected.

Christie goes on to say:

It was agreed in future I should see the jacket first and approve of it.

So we know that from this point on, Christie expected to be involved in the approval process. While I’ve never seen the jacket that she so disliked, there is a hint of it in a later US reprint where the victim certainly seems to be having the epileptic fit that she described. It makes me wonder if the original design had been floating around for a while.

Below, this was the jacket finally printed for the British first edition. Created by the artist H.T. Warren it likely was more satisfactory than the lost proof design. However, it clearly was not based on Christie’s design suggestions – as there’s no clear grave, nor body with a dagger sticking out of it.

In the States, the first edition had a very simple design – and sadly that artist is unknown. While little is known of the artist, HT Warren, he did design other jackets for different authors. As we’ll soon see with other artists, many had a stylistic element they often reused – here, to the right of the British first edition, you can see another of his jackets from 10 years later with the same bent over suspicious figure still lurking about!

1924 – Poirot Investigates. Artist: Broadhead.

Many of the early jacket designs portrayed scenes from the novel. However, for the jacket for the 1924 publication of Poirot Investigates, rather than showing a scene from one of the short stories, The Bodley Head chose to use a portrait of Poirot painted by William Smithson Broadhead that had been published a year earlier in The Sketch magazine. As a jacket, I’d argue that this is one of the most influential jackets ever on a Christie novel because of how it shaped the public’s perception of Hercule Poirot.

More importantly, we know Christie approved of the depiction as she wrote that:

[Bruce Ingram, Editor of The Sketch] also had a fancy drawing made of Hercule Poirot which was not unlike my idea of him, though he was depicted as a little smarter and more aristocratic than I had envisaged him.

Shown below is that original full page spread from The Sketch. Many fans of Christie on the screen consider David Suchet’s portrayal of Poirot to be the best. When you look at Suchet’s portrayal it becomes clear that Broadhead’s painting continues to be hugely influential in how we see Poirot today.

Karl Pike, who wrote the introduction to the 2017 reissue of ‘The Big Four’ stated it perfectly:

Many knowledgeable Christie fans consider this superb, full-length portrait, conceived and executed a mere three years into his literary career, as the best ever, unaffected as many subsequent incarnations inevitably were by stale custom, eccentric designs and oddball interpretations on stage and screen.

This portrait by Broadhead was even used by the New York Times in 1975 for Poirot’s front page obituary – the only time they ever published an obituary for a fictional character.

Christie and her publishers realised how influential the portrayal was and perhaps with an objective to let her main characters live in the minds of her readers, Poirot was rarely ever seen again on the cover of a first edition book. In fact, Miss Marple’s first short-story collection - The Thirteen Problems - published by Collins showed how much the pendulum had swung the other way … no picture of her here!

A little background then on the artist who painted Poirot, W. Smithson Broadhead. He was born in Cumberland (now Cumbria) in 1888. As a child he learned to ride, which started his life-long love of horses and with the outbreak of World War One, it enabled him to join the 1st King Edward's Horse regiment. He spent three years fighting in France. After the war, he worked in London focusing primarily on painting portraits of jockeys and racehorses – many of which are now in the National Museum of Racing in New York. While in London he also studied at the Royal College of Art and regularly exhibited at the Royal Academy. It was during these early years when working in London that he received the commission from The Sketch to create Poirot’s portrait. His art did adorn a couple of other author’s novels, but he never did another jacket for a Christie.

By the 1930s, he was commissioned by various railways to create many of their travel posters. Certainly worth pointing out is that Broadhead painted this 1934 Torquay poster for Great Western Railways. It is likely one of the last pieces of work he did in England because he moved to America at the end of that year.

1926 – The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. Artist: Ellen Edwards.The next book I want to jump to is Christie’s 7th book, but the first published by Collins – The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. Published in 1926, Collins chose to stay with the common style of the day which was to portray a scene from the novel on the cover.

The artist hired to design the cover was Ellen Edwards – while not much biographical information is known about her, she was a prolific dust jacket artist who had developed a very clear aesthetic – a light background, a single figure and a shadow.

Edwards even appears to have recycled the design she’d created a year earlier for Lynn Brock’s book Colonel Gore’s Second Case. Whether Collins knew that the cover was modified from prior work or not is unknown. (Note: images are from later reprints to give a better side by side comparison though the date of artwork is accurate).

Ellen Edwards also really liked the design of a woman, a phone and a shadow. As you can see here, she consistently reused these elements for years to come. We know that in the 1930s only wealthy households had telephones so many potential readers might have been curious to see how the phone was integrated into the plot. But that might be giving more credit than is due. It is equally possible that Ellen Edwards was just very effective at time management.

1927 - The Big Four. Artist: Derrick.

To date, the more common approach to jacket design had been to portray a scene or character from the book. In 1927, The Big Four’s jacket took a different approach and was unique it that it was also the first time the British designed jacket was used on the US first edition. From an artistic perspective, I think the design has hints of art deco with its geometric shape for the number 4 and its representation of the London skyline. The artist, Thomas Derrick, may have been influenced by designs that just emerged from the 1925 International Expo on Decorative Arts held in Paris - which celebrated both the architecture and design elements illustrated here and launched the art deco period.

The artist, Thomas Derrick, was born in Bristol in 1885, and later moved to London where he trained at the Royal College of Art - later teaching there. During World War I he worked for the Ministry of Information and painted many items to support the war effort. Today, many of his paintings are now held at the Imperial War Museum.

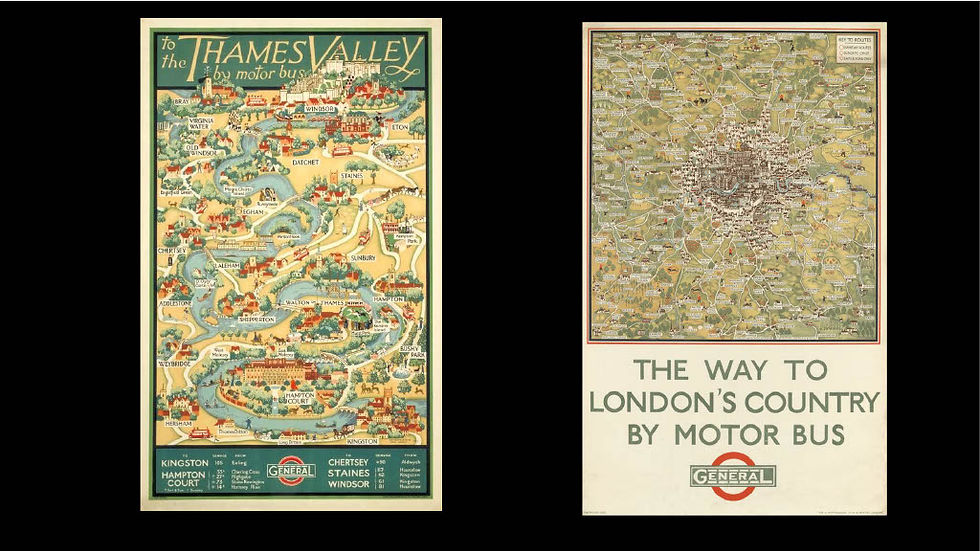

After the war he continued to paint and obtained various commissions including several jacket covers for books. One of the more notable commissions was in 1924 by London Transport to create posters promoting the use of ‘motor buses’.

He also designed this incredibly busy and detailed, but very popular poster for the British Empire Exhibition in Wembley.

In addition to designing Christie’s The Big Four, he also designed the jacket for the British edition of The Mysterious Mr. Quin in 1930. While I have no record of Christie’s thoughts about this jacket, I expect she approved of it given her love for Harlequin figurines – which you can still see in her Greenway home.

Over the years he designed numerous dust jackets and illustrated many books – a sample is shown here showing his artistic range over the years. From 1931 onwards he was an active cartoonist and frequent contributor to Punch, which perhaps explains the style he used for the book on the right. He died in 1954.

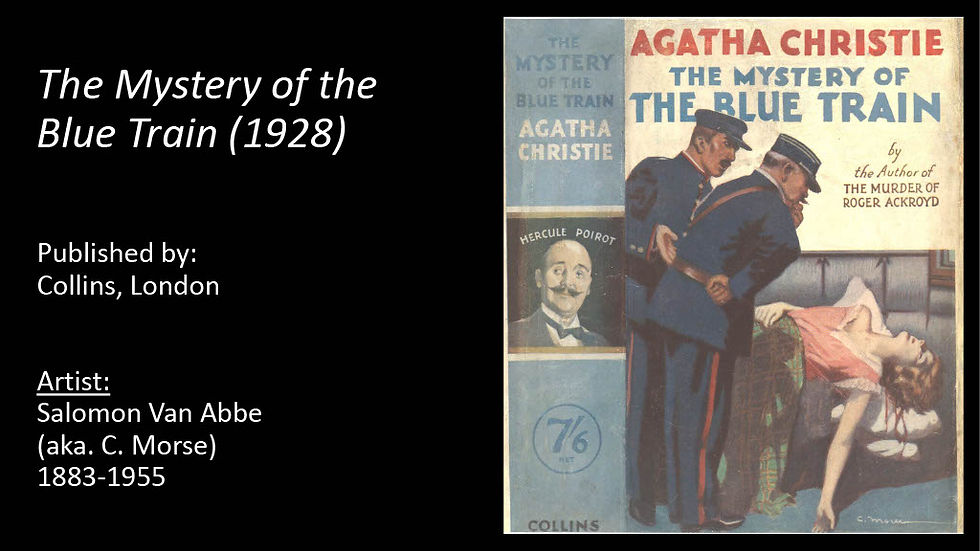

1928 – The Mystery of the Blue Train. Artist: Abbe.

The Mystery of the Blue Train reverted to the more traditional approach of showing a scene from the book – here is the UK first edition by the artist Salomon Van Abbe from 1928. While Poirot was no longer a dominant character on the front of the jacket – his image did appear on the spine.

Abbe was a prolific jacket artist – creating dozens of jackets for well-known authors including Dorothy Sayers, Freeman Wills Crofts and P.G. Wodehouse. However, it was clear he was comfortable painting police officers in blue uniforms – the two policemen in his jacket from 1922 seem to still be employed in the 1928 Christie cover on the right!

In fact, Abbe also created the cover for the first paperback of Christie’s The Murder on the Links – published in 1932 by The Bodley Head. Here we also see Abbe’s ubiquitous policeman. It’s also interesting to note that Abbe clearly was not specifically contracted to design artwork for Collins given that The Bodley Head still controlled the publishing rights to Christie’s first six books.

Abbe also created a portrait of Poirot – one that made it onto the Bodley Head reprint of Poirot Investigates and also as an internal illustration in a Collins Book Club edition of Dumb Witness. That he was able to sell the same image to two different publishers is rather surprising. Going forward we rarely ever see any portraits of Poirot on or in Christie’s first edition books.

1929 – The Seven Dials Mystery. Artist: Wallcousins.

Christie’s next novel was The Seven Dials Mystery. I love the design of this cover – it’s so evocative of the roaring 20s. The artist was Ernest Wallcousins – an illustrator and later a famous portraitist and landscape painter.

As a graduate of the Westminster School of Art, some of his early commissions were to design posters for the London Underground Group – the style of which became ubiquitous across transport posters of the 1920s and 30s. Papers in The National Archives show that he was the designer of the famous Keep Calm and Carry On poster, as well as several other similar posters. He was also commissioned by Odhams Press to paint Winston Churchill's WWII victory portrait in 1945 for their Victory Book. The picture was painted from life in the Cabinet Room.

1930: Giant’s Bread. Artist: Macadam.

1930 saw the publication of Christie’s first novel under her pen name of Mary Westmacott. The jacket was designed by Margaret Macadam – with its art deco stylistic interpretation of the musical instruments from the novel. As we saw with Thomas Derrick’s jacket for The Big Four, there was shift occurring in jacket design away from the portrayal of a scene from the novel.

Little was known about the artist until 2016 when an archive of her work was discovered, within which was the original painting she made for Giant’s Bread shown in the middle. We now know that she was a member of The Society of Women Artists and had received a scholarship to the Royal Academy Schools. I think Christie would also have been pleased to know she served as a Nurse for the Voluntary Aid Detachment in World War II.

1932: Peril at End House & more. Artist: Morris.

[Slide] Jumping across the pond to the States, the next artist I want to discuss is Beth Krebs Morris. She designed three Christie jackets – the first time an artist created more than two jackets for Christie. What’s interesting to observe here is how Christie’s name gets larger and larger on the book. I interpret this as the publisher is now fully aware that Christie’s name alone will sell a lot of books and the shift to start capitalizing on this is becoming clear.

Little is known about the artist, though she was clearly highly respected and successful. Records show that she hosted a radio show on NBC about how to illustrate books, and she was also included in an exhibit in the DeYoung Museum in San Francisco – along with noted artist Diego Rivera – which is great to see as it affirms dust jacket art was being recognized an art form.

In the 1930s she was a prolific designer of jackets for many different US publishers – not just Dodd Mead. Here is a sampling of a few of her other jackets and you’ll notice how small the authors’ names are here compared to Christie’s books.

1934: Why Didn’t They Ask Evans. Artist: Cousland.

1934 brought to market one of the most shocking covers on a Christie to-date – an image of the character Alan Carstairs, dying after falling off a cliff. The artist was Gilbert Cousland. I love this cover – it’s so unique – but I always felt it had a slightly odd look to it. It wasn’t until I really started researching Cousland’s work that I came to realise this was likely a colourized photograph – which appears to be the first time a photograph of any type had been used on a Christie book.

By the early 1930s, Cousland was already an established photographer, working out of the Briggs Studio in St. John’s Wood, London. His breadth of work is shown here – ranging from images now held in the V&A’s permanent collection to commercial work doing photographs for Boots ads.

But his greatest commercial success was through a string of children’s photographic picture books – a small sampling of them shown here. He won numerous awards and wrote lots of academic articles about photography.

In 1933, he married “Mainie” Thompson and shortly after they moved into the Isokon flats at Lawn Road, in Hampstead, living here from 1934 to 1938. I bring this up because we know Christie also lived here – but later from 1941-1947 – but a small world and an interesting connection. When the Couslands' lived here so did Marcel Breuer – the famous modernist architect and furniture designer. While I’m on a tangent here, I found it interesting that the Couslands’ owned a lot of Breuers furniture – which was donated to the V&A and is held in their collection.

One final observation about Cousland’s jacket is that I like to think that when George Chrichard created the cover for the 1963 Book Club edition of The Clocks, he paid homage to the cover created by the man who had the same initials as him from many years earlier.

Next Instalment: Part 2 - The Art and Artists of Agatha Christie. The second and final instalment of my presentation will be published within the next week. It will take us all the way through to the 1970s and the last books published while Christie was alive and able to provide input. I do hope you enjoyed this first instalment. Feedback and corrections are most welcome. Please email me at collectchristie@gmail.com .

Other News: If you haven't been listening to the new podcast from the organizers of the International Agatha Christie Festival titled 'Agatha Christie in Devon', then you are in for a treat. It is available on Apple podcasts, Amazon Music and Podbean (link to all). There will be 10 episodes in all, with a new one released weekly. I was invited to participate in this podcast series and was featured in Episode 5 (Dartmoor) sharing my thoughts on why I love Agatha Christie. I hope you enjoy the whole series.

Subscribe & the Socials:

If you are not a subscriber to my website, please consider subscribing here: link. This ensures you receive an email any time I write and post an article. Also, consider following me on X (formerly Twitter) @collectchristie and on Facebook (link). The content varies across platforms.

Comments